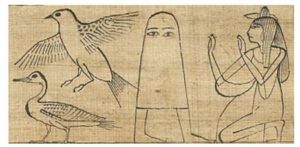

The ghost-like form of Medjed is illustrated on the Greenfield papyrus with a goose on the left (British Museum).

How can a story connect a Goose God, a Ghost God with laser-blasting eyes and the creation of the universe? Well, Egyptian mythology has the answer. Many stories were created to comfort the living for the passing of their loved ones that impacted beliefs about the afterlife. Death may have been a certainty for the ancient Egyptians, but what came after was not. At first, the afterlife was thought to be a paradise called “The Field of Reeds” where humans traveled on a one-way road from birth to death. As people change with age so does their form: there are seven (or even nine) aspects of a person with Ren as one’s secret name given by the Gods that was revealed after their passing. Along with this view went an understanding of disembodied spirits – ghosts – that were as much of a reality as any other aspect of existence.

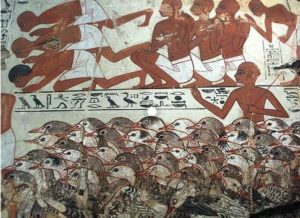

Nebamun viewing his geese and cattle, showing the geese and servants. Painting from the tomb-chapel of Nebamun, accountant in the Temple of Amun (Karnak), circa 1350 BC, Ancient Egypt (British Museum).

The ghosts suffered as the result of the neglect of their loved ones. Stories about revengeful spirits become more evident after the skepticism that marked the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030-1650 BC). Questions arose regarding an afterlife of eternal peace: if there was no paradise then where did people’s souls go when they died? The most prevalent answer seems to be, nowhere. These vengeful spirits seemed to have a leader: Medjed (meaning “The Smiter”) mentioned in the “Book of the Dead” of the New Kingdom (ca. 16th–11th c. BC).

In the Greenfield Papyrus, we read: I know the being Mātchet [Medjed, shooting rays of light from [his] eye, but who himself is unseen …[..].

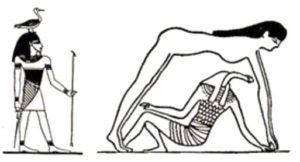

The creation of the universe was also related to a very fearsome animal: the goose and, specifically, the Egyptian goose. These birds were chosen as a part of a cultural complex that emphasized the importance of the sun as a source of vitality but also represented prosperity and fertility. According to legend, the “Great Cackler” or “Great Honker” or “Chaos Goose” cackled so loudly that laid an egg that became the sun at the dawn of time. The egg was linked to Ra, and later he and the Goose god were seen as one. This deity was connected to the underworld through the Snake God, father of Osiris, ruler of the netherworld and figure of resurrection. At the end of the New Kingdom, the figures of resurrection dominated the Egyptian tomb art with representations of geese as they could fly towards heaven as celestials.

The two forms of the god Geb: (left) in his human form with a goose on top of his head and (right) with his half human-half snake form under his sister and lover the sky goddess Nut (Dover Pictorial archive on Egyptian Designs, Mineola, New York, 1993).

The aspect of death changed for the ancient Egyptians as it happened for many other cultures. The linear connection of life with another world became something uncertain and fearsome. Ghosts started to interfere and complain about their constant state of nothingness. The only way to keep them happy is by honoring them in their forever homes: their graves. The sky, the universe and time were a result of a creature of chaos and fertility which was also associated with the underworld. The concept of rebirth starts to emerge and life begins to be perceived as a circle.

As it seems, the Egyptians had already understood Marvel’s concept that “time, space, reality – it’s more than a linear path. It’s a prism.”