There are moments during your PhD where you wonder what on Earth you’re doing. You don’t want to get out of bed and work on this topic that does not interest you anymore. You regret having obeyed your maths teacher who forced you into sciences, now convinced you’d be so much more happier working on something completely different. When that happens, I remember why I chose that path. How as a child I could sit in front of Cousteau’s documentaries, eyes wide open in excitement while watching deep sea creatures. How I dreamt of crossing the immensity of the far north Canadian wilderness, alone on a sledge with my team of dogs while the auroras dance above my head. How I held my breath while reading Shackleton’s account of their escape after the Endurance was destroyed by the ice, and how somber I found Scott’s attempt at coming home after the race to the South Pole. It is the last story that I want to share with you today.

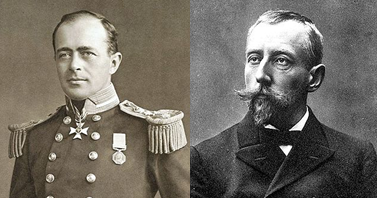

First, let’s meet our contestants! Robert Falcon Scott is a British Royal Navy officer from Plymouth. In his early thirties he was in command of the Discovery expedition that reached Antarctica in 1902. He marched to 82°S with Shackleton, and the following year discovered the Antarctic Plateau. Ever since his return to the UK in 1904, he’s been a polar hero! In 1908 he starts talking about going back to Antarctica and conquering the South Pole for the glory of the British Empire. In his last Antarctic mission, Scott was not impressed by the dog sledges. Hence this time, he decides he will use… ponies! And as the 20th century is just starting, Scott wants to be modern and takes some mechanical sledges as well. On 15 June 1910, the Terra Nova leaves Cardiff Antarcticabound. As they arrive in Australia in October, they are informed they are not alone in the race, and their opponent is no rookie. The Norwegian Roald Amundsen was onboard the first expedition to winter in Antarctica (1897-1899). He led the first mission that finally found and successfully traversed the Northwest Passage (1903-1906). In 1910, having issues fundraising for his exploration of the North Pole, he decides to reroute and leaves Oslo onboard Fram on 5 June 1910, sending a telegram to Scott to politely inform him that he’s also en route to the South Pole.

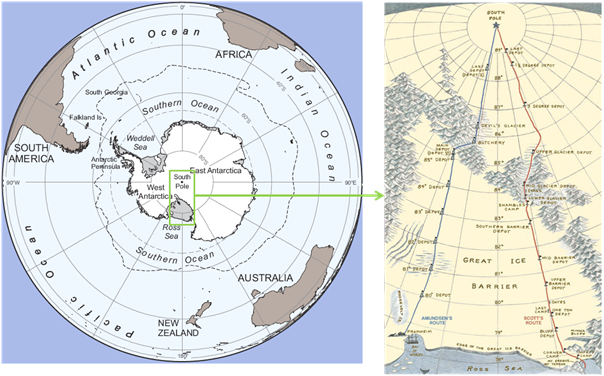

The race does not begin yet. For both teams, the first season is much-needed preparation time. They both install supply depots on the way to the pole, Amundsen seemingly easily whereas Scott loses six ponies and a motor sledge. Amundsen departs his base camp on 19 October 1911 along with four men, and 52 dogs that they plan on killing on their way to have fresh meat. Scott departs on 1 November 1911 with a far larger support party that shrinks as groups regularly turn back as planned. In Britain, they have scientifically calculated how many calories they will need each day and are fairly confident in the food rations they carry. Amundsen reaches the Polar Plateau on 21 November after discovering a new fast route through the Axel Heiberg Glacier; Scott and his four comrades finally reach that same plateau a month later, suffering from bad weather, having faced really tough terrain and forced to admit that his ponies were useless in Antarctica and that the food rations had been largely underestimated. By that time, Amundsen was already at the South Pole! His party and the remaining 16 dogs reach the pole on 14 December 1911, leave a tent and a letter stating their achievement, and quickly turn back to announce their success to the rest of the world. Scott finally reaches the pole on 17 January. By that time Amundsen is only a week away from his base camp.

Left, Antarctica in relation to the rest of the world (image National Geographic). Green box and right show the Ross ice shelf region and beyond, where the race to the South Pole happened: blue Amundsen’s route, red Scott’s (image artofmanliness.com).

Now think like Scott for a moment. This is your big expedition that will bring you immortal fame, but everything has gone wrong since the beginning. The ship nearly sank off New Zealand. Your equipment broke even before the race started. Your ponies were a terrible mistake. Your authority keeps being disputed. You suffered from sheer bad luck with the weather and the terrain. You’re freezing, hungry, exhausted, yet finally here it is! You’ve made it to the Pole!!! Oh, but you’ve lost the race. Amundsen was there a month ago. While you’re stupidly wasting your time here, he is nearly back. Soon he will announce his exploit to the rest of the world, and everyone will know you failed, by quite a lot! Your career is ruined. The whole establishment will mock you and reject you. You are done. You are a loser.

There are various theories to explain with hindsight why Scott’s march back was such a catastrophe. For example, despite similar incidents in the Arctic (that I may tell you about in another snack), the British refused to get proper equipment, in particular footwear and tents, that would fully protect them against the harsh cold, thinking they have no lesson to learn from native Greenlanders. Hence frostbites and hypothermia were frequent. So was scurvy, due to their obsession with pemmican instead of hunting seals or killing their dogs to have fresh meat. But it’s only recently that the psychological aspect has been pointed out. Scott’s is a hugely depressed team that leaves the pole on 19 January 1912. Despite bad weather they actually make good progress at the beginning, until Evans falls on 4 February. He dies two weeks later after a second fall. The rest of the party reaches the meeting point for the dog team and awaits them. But the dog team and its food supply does not come, because of a chain of poorly/non executed orders.

By 10 March, after two weeks of waiting in increasingly bad weather, the frost-bitten, snow-blinded, starving party restarts its march north. It is a slow march: Oates’s toe is so frostbitten he can hardly walk. Aware that he would cause everyone’s death as they would not abandon him, Oates commits suicide on 16 March by voluntarily leaving the tent and exposing to the freezing winds; he is never to be seen again. The remaining three men walk an extra 20 miles in three days despite Scott’s toes also becoming frostbitten. They make their final camp on 19 March 1912. They are only 11 miles away from their food depot, but they will never leave the camp again. The raging blizzard forces them to choose between dying of cold exposure or dying of starvation. They chose starvation. Scott’s diary, found several months later by a search party, reveals that they died on 29 March 1912.

Now, you probably feel quite depressed and are wondering how I can find strength in that story. The thing is, I’ve always been longing for adventure. I wish I were born a few centuries ago, sailing the seven seas as a pirate or discovering new land every time I got lost at sea (I know, technically as a female I would probably not have been allowed to do that, so in fact I’m happy living nowadays instead). But this story is a constant reminder that Antarctica still is mostly Terra Incognita, very hard to reach (especially if you’re a pony) and not forgiving. Although 100 years after that race, conditions have improved for the better, Antarctica is still totally disconnected from the rest of the world. If your ship sinks or if there is a medical emergency, the closest land is days away. Just think that meanwhile in the International Space Station, they only need a few minutes to go back to Earth if needed! In the polar oceans, if you fall into the water, you will die of hypothermia very quickly (or get eaten by an orca). You hardly have any internet, and very poor satellite phone, so people can easily feel lonely, homesick and depressed. But it is also such a magical place! You can stare for hours at the ice and never see twice the same colour or shape. You can see the whales play around your ship and the albatrosses follow you even days after you have last seen land. As you break the ice, you can hear the penguins complain and suddenly see a dolphin surge just in front of you to breath. You feel very close to these heroic explorers, walking in their footsteps, experiencing the same issues yet marvelling at that same near-alien frozen world. And that is what makes me a happy polar scientist -that, and penguins: