“Could you check out the weather for a hike?” shouts my friend from the other room. So I open my phone’s weather application to do so, totally taking that kind of service for granted. Only 20 years ago people still had to look at thermometers (and there even was a time when those weren’t common), and you wouldn’t have expected everyone to know how to read such a gadget. Weather apps and thermometers have become so normal that we forget they are part of a long process, and scientists are working really hard to provide us with devices that will be normal in our everyday life. They kind of have a future look on things that might be quite common someday.

When the thermometer was developed at the beginning of the 16th century it was highly innovative. Today, technology is constantly changing, and more often than not scientists are the first to know. As a student of earth science, I have been surrounded by fairly new, or at least yet not commonly known technology. And it comes for me being lucky as I got to do my internship at the University of Bergen. Soon I expected everyone to have heard about the device I am working with. Instead I heard “What is a SODAR?”; “What does a SODAR do?”; “What is a SODAR good for?”- Being surprised about few people knowing it I realized how fast I had taken it for granted. So let’s introduce this technology.

SODAR stands for Sound Detection and Ranging and measures the wind speed of the  upper atmosphere from the ground. It was developed in 1946 for investigating the so-called atmospheric boundary layer, which is the compartment of the atmosphere that is constantly affected by the ground underneath. That makes it relevant for us, the ones living in this intersection between earth and atmosphere. Observing its processes is not easy. Unlike measurement devices like thermometers set inside a traveling balloon (radiosondes), which detect one vertical profile at a designated time, a SODAR can repeat this. So you get a profile for the same spot every few minutes. So how does it work?

upper atmosphere from the ground. It was developed in 1946 for investigating the so-called atmospheric boundary layer, which is the compartment of the atmosphere that is constantly affected by the ground underneath. That makes it relevant for us, the ones living in this intersection between earth and atmosphere. Observing its processes is not easy. Unlike measurement devices like thermometers set inside a traveling balloon (radiosondes), which detect one vertical profile at a designated time, a SODAR can repeat this. So you get a profile for the same spot every few minutes. So how does it work?

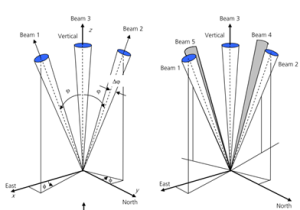

The SODAR sends out sound pulses in a specific (and unpleasant sounding) frequency, mainly vertically  but also in northern, eastern, southern and western directions. However, these only differ from the vertical beam by about 20°. As the air above us is neither constant in temperature nor in density, these fluctuations scatter back the sound waves. The SODAR receives this backscattered signal that has now shifted in frequency (Doppler Shift). Using these deviations and the traveling time of the waves through the atmosphere, it is possible to calculate the wind. Though SODAR provides this information a SODAR RASS can do much more.

but also in northern, eastern, southern and western directions. However, these only differ from the vertical beam by about 20°. As the air above us is neither constant in temperature nor in density, these fluctuations scatter back the sound waves. The SODAR receives this backscattered signal that has now shifted in frequency (Doppler Shift). Using these deviations and the traveling time of the waves through the atmosphere, it is possible to calculate the wind. Though SODAR provides this information a SODAR RASS can do much more.

The RASS (Radio Acoustic Sounding System) is an extension of the SODAR for measuring the temperature. The working principle is similar to the SODAR, except that the RASS sends out electromagnetic waves instead of sound waves. The waves reflects at the sodar acoustic signal that travels with the sonic waves and so measures the speed of the sound, which changes with temperature. For example, having a vertical profile helps to find the parts of the atmosphere where temperature is increasing (Inversion).

An inversion is not the usual course and can act like a cover over a city, gathering aerosols underneath. On a regional scale this is influencing air quality and therefore our health. But even with just the wind information, it could be quite helpful in our everyday life. Really high wind speeds might not give us the best day for a hike or an umbrella. One might think we could use the SODAR information for predicting such days.

Prediction Models start with the actual state of the atmosphere. A thorough understanding of the state of the air above us is important, because small mistakes at the beginning of the calculations can result in big changes in the outcome (chaotic system). The SODAR’s information could be used to get the best possible knowledge of the atmosphere’s condition. SODARs are normally installed in terms of a project. They are used at wind farms or for verification of specific weather events. A SODAR needs a lot of space and an accurate set up, so it is not made to be mobile. Also it is very stable so you don’t need to worry for it to be easily “gone with the wind”.

However, if we want to use it in the context of weather apps, it may not be so doable. Making an annoying sound is one of the SODAR’s characteristics. Hardly anyone wants to have a device standing in its yard that “beeps” every 10 seconds. You can still hear the SODAR a 100m away, so lots of measurements are made in areas where not too many people may be complaining. As it turns out you will find a SODAR in places like the Arctic and Antarctic.

In 2004 Anderson constructed and tested a SODAR in the Coats Land in Antarctica for over 2 years. That SODAR was the first to observe the katabatic wind during wintertime in those regions due to remote sensing. One of the great advantages was the unmanned usage of the device.

My SODAR, all lonely and independent but probably cold as well, just got installed on Svalbard in August 2015. It is supposed to stay there until summer 2016. Let’s hope it will go on working fine and who knows, maybe its measurements will be accessible for everyone and taken for granted someday.

Picture References (01.10.215):

Figure 1: http://sasakihome.info/~sasaki/TibetSiteSurvey/Instrument_SiteMonitor/00Instrument_index.html

Figure 2: https://isaacbrana.wordpress.com/2012/02/18/sodar-operation-limitations-12/

Figure 3: http://horizon-magazine.eu/sites/default/files/Svalbard.jpg

Other References (19.10.2015):

http://www.livescience.com/39841-temperature.html

PHILIP S. ANDERSON, RUSSELL S. LADKIN, AND IAN A. RENFREW, An Autonomous Doppler Sodar Wind Profiling System, British Antarctic Survey, Cambridge, United Kingdom, Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology (Volume 22 ) September 20015