Shrub encroachment is threatening the livelihoods of billions of people world-wide. This is the drastic but established view. This view, however, has recently been challenged by David Eldridge and colleagues. Through their work we now have a better understanding of the global effects of shrub encroachment on ecosystems, but why is shrub encroachment occurring in some places and not in others? A global answer to this question has yet to be found.

Shrub encroachment usually means an increase in woody cover within grassland and savanna ecosystems. Such encroachment has been puzzling both ecologists and farmers for some time. The first recorded observations of African savanna rangelands experiencing encroachment by woody plants date from the early part of the 20th century. These observations then became an increasing focus for scientific studies over time, eventually resulting in entire research projects being devoted to this mysterious phenomenon.

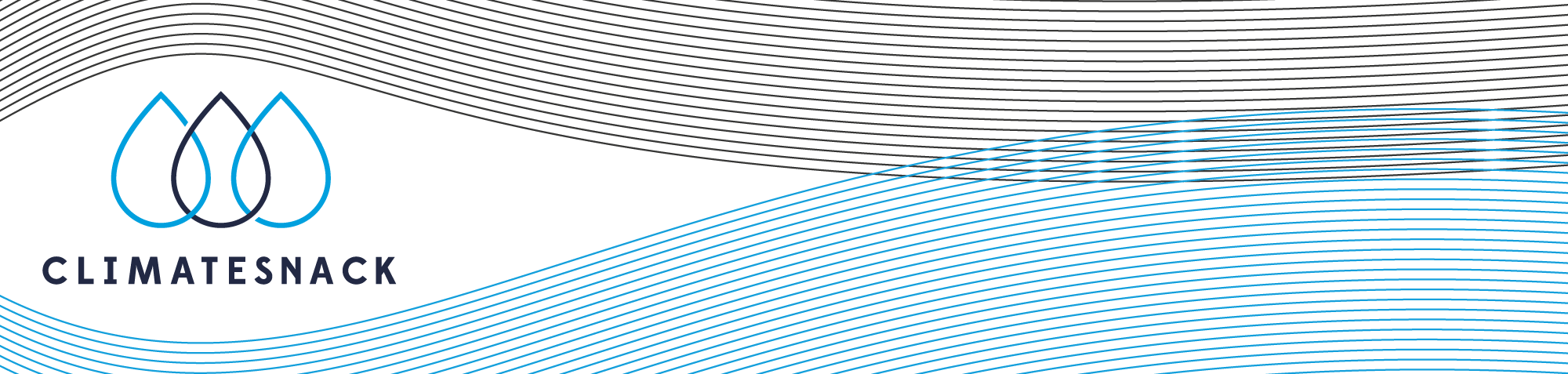

Open savanna rangeland (left) and heavily shrub-encroached rangeland (right) in Namibia. Note the virtual absence of grass under the dense shrub cover on the right.

The increase in interest has mostly been triggered by the consequences of shrub encroachment. People traditionally using grasslands and savannas as feeding grounds for their livestock suddenly had to deal with ever decreasing forage as the grasses previously used by their cattle and goats were increasingly replaced by shrubs.

These undisputed adverse effects of shrub encroachment have led to the common perception that it is an undesirable phenomenon in farmland areas or animal feeding grounds, and that it has a detrimental effect on ecosystems in general. However, a recent review of the global effects of shrub encroachment on ecosystems has opened up the debate to consider both negative and positive effects. Surprisingly, the review failed to find any consistency in either the positive or the negative effects of shrub encroachment. It instead concluded that the degree to which it is considered to affect ecosystems, and ultimately human livelihoods, depends to a large extent on the individual ecosystem and which parts of the ecosystem, or services provided by the ecosystem (e.g. carbon sequestration, forage production), are considered to be desirable.

As close as we may now be to understanding the global consequences of shrub encroachment we are still a long way from understanding its causes on a global scale. Although we may in some cases understand the causes on a local scale.

Scanning through the scientific literature reveals a number of recurring explanations for shrub encroachment. Amongst the most common explanations are high grazing pressure, fire suppression, increasing rainfall, and rising levels of CO2 in the atmosphere, all of which have been reported in case studies.

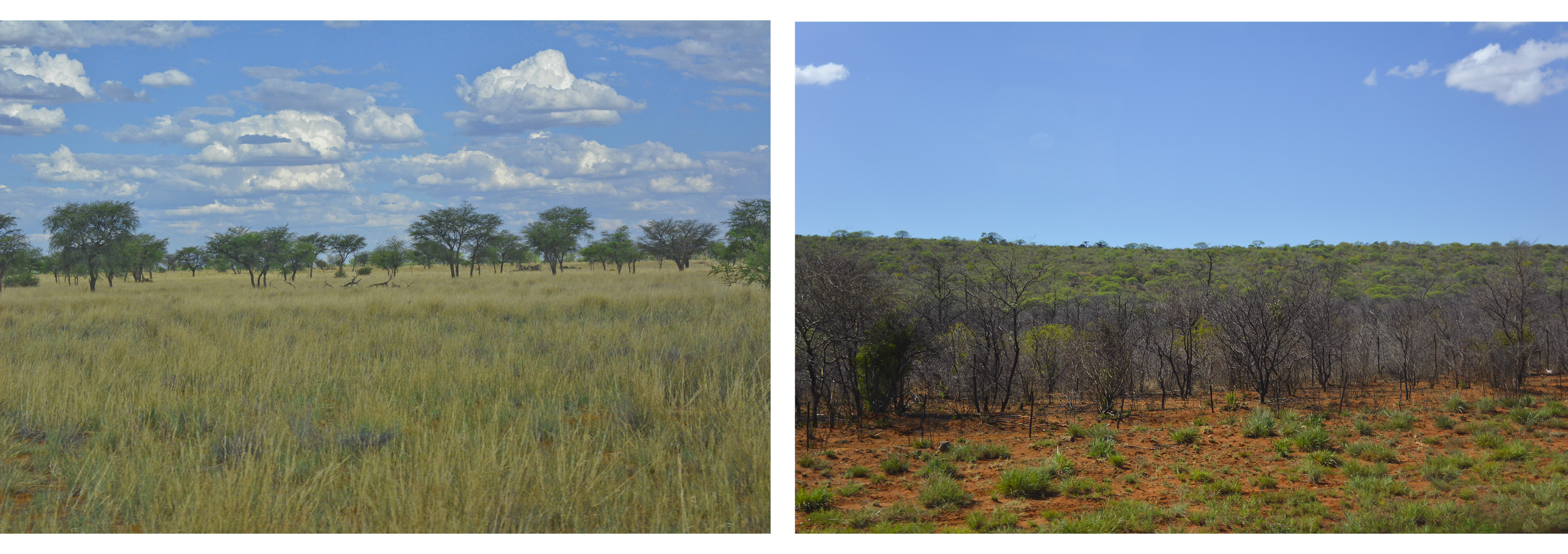

Comparison between recently burnt shrubland (right) and shrubland that burned 16 years ago (left) in Waterberg Plateau National Park, Namibia. Note the higher shrub density on the left, but also how quickly shrubs are regenerating on the right. The dead shrub residues on both sides are due to recent frost mortality.

The blame for shrub encroachment has most commonly been assigned to high grazing pressures. Under this scenario grass is assumed to be replaced by shrubs: the more grass is eaten, the more shrubs are able to grow. This explanation has in later studies been extended to include fire as a causative factor: the less herbaceous fuel there is the smaller the number of fires, resulting in shrubs (and their seedlings) being less likely to be destroyed by fire. In other words, fire appears to play an important part in encouraging the growth of some plants at the expense of others.

Robert Buitenwerf and colleagues found that increasing levels of CO2 were mainly responsible for growing woody plant densities in South African savannas. The underlying assumption was that the competitive ability of woody plants increased relative to that of grasses as a result of increasing atmospheric CO2 levels. One of the most comprehensive studies was carried out in Swaziland by Roques and colleagues, who came to the conclusion that a combination of high levels of grazing, a reduction in fires, and increased rainfall was needed for shrub encroachment to occur.

An important step was taken by the Journal of Ecology towards understanding the global drivers of shrub encroachment. A number of interesting studies in their special issue on grassland-woodland transitions have added to our understanding of the causes of shrub encroachment. But as pointed out by the special issue editors (Osvaldo Sala and Fernando Maestre), this is only one step towards achieving a global understanding of the drivers behind shrub encroachment.

What appears almost certain today is that there is not just a single factor controlling shrub encroachment, but that it is more likely to occur a result of a number of different factors, with their relative importance varying from one site to another.

Thousands of new data points are being added on a daily basis to global climatic, edaphic, and land use databases (and many more). These data should now enable us to determine which factors are particularly important for shrub encroachment, and this in turn should finally give us an answer to the question of why shrub encroachment is occurring in some places and not in others.

Understanding the consequences of shrub encroachment and demystifying its causes globally will enable people all over the world to then decide whether or not they want shrubs and how best to achieve their desired results.