It is summer, my favorite time of the year, and I’m in Munich, my favorite city in Germany. With all the sunny days and the warmth, Munich somehow seems too blessed to be stressed. The streets pulse with life, filled with people sitting outside and enjoying the warm summer evenings. Shallow sounds of music sometimes blend in with the happy chatter swirling around. The cozy atmosphere of comfort, peace and acceptance that is special for the city has long since become a major part of the Bavarian culture.

Of all the things Munich is known for, beer might be the most famous. At the Oktoberfest alone, more than 7 million liters of the precious liquid are being consumed every single year. Beer brewing has a glorious history in the region, and the triumph of the beer is mainly ascribed to the local climate conditions, which are particularly favorable for the growth of crops like hop and barley. The oldest local brewery in Munich was founded in the beginning of the 14th century, and still brews today. Since the 16th century, the ‘Reinheitsgebot’ (the German purity law) is in effect, stating that beer entitled with it is brewed based on nothing else than hop, barley, and water. And where better to enjoy a tasty, cold beer than in one of the city’s many beer gardens sitting on a bench underneath a big chestnut tree, whose green roof spends pleasant shadow on a hot, sunny afternoon?

These beer gardens are a specialty of the region, and have an old tradition greatly dependent on the favorable climate. In the 19th century, King Ludwig I constrained any beer brewing to the winter months to ensure that temperatures where low enough for fermentation. The breweries built roomy cellars along the river Isar to store the beer for the summer months, and planted huge trees above ground to protect the cellars from the summer heat. It didn’t take much time until they also set up simple benches and tables so people could sit down and enjoy their newly purchased beer. These initial beer gardens soon turned into popular meeting points for the locals. Out of consideration for local restaurants, the breweries were not allowed to sell food in the beer gardens, which is why people could bring their own picnics but had to buy the drinks. And even though the rules aren’t as strict anymore, this is how it still works today, marking an important part of the social culture of Munich: bring your food, buy your beer, and enjoy your sunny afternoon!

But it is not only Munich where local climate creates the culinary culture of drinks. Just think of wine from Italy, whisky from Scotland, or sake from Japan. There also seems to be something special about the prevailing climate conditions in Munich and the local beer culture. Because the city has plenty of both, beer gardens and summer days of sunshine, which warm the air until far out into the nights. But why are the summers in Munich so sunny? What is it that is so special about the climate in Munich that its culture of sitting outdoors and drinking beer makes it famous all around the globe?

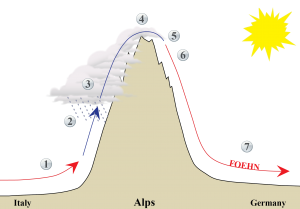

It all starts in northern Italy with southerly winds and a lot of rain. And it ends in southern Germany with sunshine and exceptionally warm downslope winds. In between, there are the Alps, and a fortunate series of events shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2 Schematic illustration of the Alps showing the evolution of warm, dry Foehn winds on the leeward side (modified from Sebastian Ludwig, unpublished).

Warm air coming from the south meets the prominent mountain range of the Alps (Position 1). This massive barrier forces the air upwards, and due to decreasing atmospheric pressure, the air cools (2). The rate at which the air cools with altitude is defined as the adiabatic lapse rate, and for dry air this rate is a cooling of 1°C per 100 m altitude.

The moment the air has cooled enough to reach the dew point, it condenses, and cloud droplets continue to grow until they fall as rain (3). Rain of this type is called orographic rain, and it significantly changes the situation, because the adiabatic lapse rate of 1°C/100 m is only true for dry air. For moist air, the temperature sinks at the saturated adiabatic lapse rate, which is around 0.65°C/100 m. This is because as the air condenses, it releases latent heat and slows the cooling. Back in the Alps, this means that the moist air in the clouds cools slower as it rises than the dry air below the clouds. The moist air continues to rise and slowly cool until it reaches the top of the Alps (4). Then it starts to sink again on the northern side of the mountain range – and becomes warmer (5).

Having released vast amounts of moisture as rain, the sinking air reaches its’ dew point at a higher altitude at the leeward side of the Alps (6). In technical terms, a faster (dry) adiabatic lapse rate of 1°C/100 m applies early on for the sinking air, instead of the saturated adiabatic lapse rate of 0.65°C/100 m. The air therefore warms up substantially when it sinks on the northern side of the Alps, and the winds finally reaching the lowlands to the north are comfortably warm (7). They are called Foehn winds and bring dry, sunny weather to southern Germany, which is the reason why the climate in Munich often is so amiable during many days of summer.

This weather phenomenon is not constrained to the Alps only. Another prominent example is the Sierra Nevada mountain range in California, where west winds from the Pacific cross the summits. However, the leeward slope is disproportionally larger here, as the region east of the mountains lies below sea level. In contrast to Munich, the air sinking down the leeward side of the Sierra Nevada therefore warms up to a degree that is far more than needed to create decent beer garden weather. In fact, this regions climate conditions count as the hottest and driest in North America, creating a desert known as the Death Valley.

In contrast to the Death Valley, the climate in Munich constitutes a fairly small risk of your beer evaporating in the summer heat. So, as long as you drink your beer fast enough it doesn’t warm up, Munich is a living example of how favorable climate conditions can play an important role in establishing traditions that benefit a region’s social life, creating local culture that is world famous and makes the city the very heart of hospitality and warm welcome. And now, if you excuse me, I have to go and sit with some friends under green trees on a wooden bench with a cold beer in front of me, on this mild summer evening… PROST!